|

| |

SEA VIXEN

All visitors with an interest in the Sea Vixen

should visit Martyn Dean's excellent site, the address of which is in our

favourite links page. It may also be accessed by clicking

HERE.

From the November 2004 issue

Back to index

De

Havilland Sea Vixen

De

Havilland's mighty Sea Vixen was the first British

aircraft to be designed as an integrated weapons system,

and the Fleet Air

Arm's first swept-wing all-weather fighter. Despite a

tragic � and very public � accident to its predecessor,

the D.H.110,the type completed a highly successful

career. TONY BUTTLER traces the development of

the radical twin-boomer.

|

|

"On

February 20,1952,WG236 was taken beyond Mach 1,

becoming the first operational-type aircraft, the

first two-seater and the first twin-engined aircraft

to break the 'sound barrier'" |

T

HE

ROYAL NAVY'S (RN) post-war quest for a radar-equipped

all-weather fighter was a long-drawn-out affair. A new

Naval Staff Requirement, NR/A.14, and Specification

N.40/46 were issued for proposals in January 1947,

calling for a twin-jet naval nightfighter to replace the

de Havilland Sea Hornet piston fighter, with a top speed

of at least 500kt from sea level to 20,000ft and a

maximum all-up-weight of 30,000lb. The highest possible

|

manoeuvrability was requested, and it had to be able to

land and take off from carriers by day or night.

Proposals were received from Blackburn, de Havilland,

Fairey, Gloster and Westland.

De

Havilland's project, given the type number D.H.110, was

a variant of a design first submitted in March 1947 in

response to RAF nightfighter specification F.44/46. The

RAF D.H.110 had two 7,000lb-thrust

Metropolitan-Vickers F.9 engines (later the Armstrong

Siddeley

|

Sapphire), four cannon and airborne interception (Al) Mk

9D radar. Its span was 49ft 6in, length 47ft 11 in,

gross wing area 640ft. all-up-weight 26,3501b and

estimated top speed 570kt (Mach 0-86) at sea level and

543kt (Mach 0-90) at 25,000ft, The D.H.110 was

eventually selected as the winner of the RAF

requirement, but a Gloster design was also accepted,

later becoming the Javelin (see Database, January

2003 Aeroplane). Three RAF D.H.110s were planned,

but by

(continued

below left column)

|

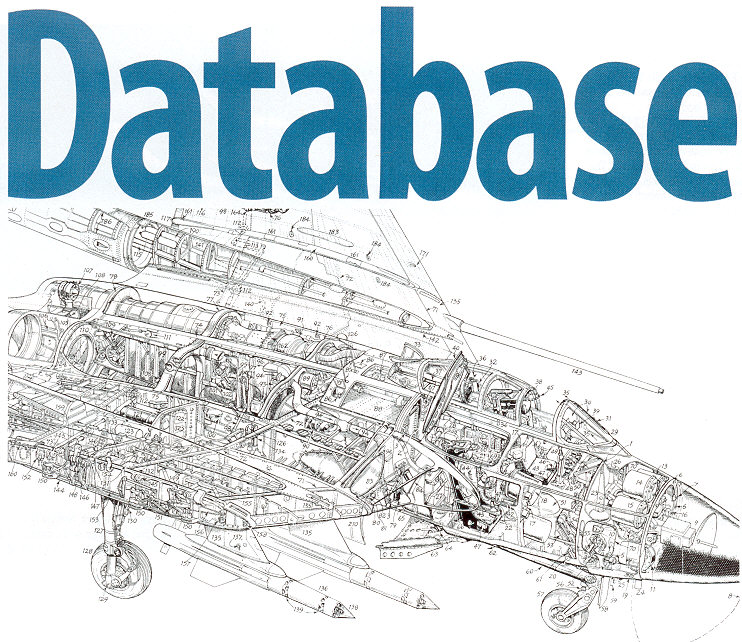

ABOVE

Arthur Bowbeer's magnificent cutaway illustration of the

Sea Vixen from the February 5, 1960, issue of Flight.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

January 1948 the armament and radar requirements

were under drastic review; F.44/46 was replaced by

F.4/48, and by July the Rolls-Royce

Avon had become the D.H.110's lead engine.

The RAF and

RND.H.110s were

essentially

the same apart from specific naval equipment and

some alterations made during 1947. The

navalised

D.H.110 was proposed in

September

with a swept-forward tail

surface

expected to be better

structurally

and aerodynamically than

the RAF

version's "straight tail". The

two crew were

seated side-by-side and slightly staggered, and four

20mm

Hispano cannon were housed

under the

cabin floor. De Havilland's

Vampire and

D.H.108 experience had

led to the

conclusion that wing

sweep was

essential to achieve the Mach 0-87 required by the

RAF nightfighter, so a sweep angle of 40� at the

quarter chord would easily cover the Mach 0-82

requirement

in N.40/46.

An

N.40/46 Design Study

|

|

|

|

|

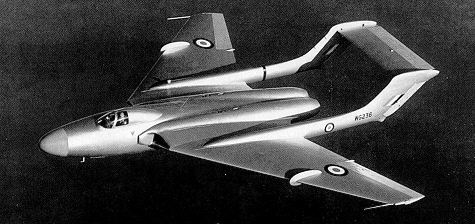

ABOVE The first D.H.110

prototype, WG236, which

made its

maiden 46min flight at Hatfield in the

hands of

John Cunningham on September 26,1951,

and which

threw the whole D.H.110 programme

into jeopardy

after its fatal crash at Farnborough

the following year.

LEFT Designer J.P. "Phil" Smith,

responsible for the Sea Vixen at Hatfield until its

move to Christchurch. He was also co-designer of the

pre-war Moth Minor.

|

public during the following month. The observer was

now housed inside the fuselage, with just a small

window to look through. At this time the screens for

the new airborne radars needed dark conditions for

ideal viewing, which sentenced the operator to a

world devoid of much light and also resulted in an

offset canopy for the pilot.

|

|

|

Conference held on December 15, 1947, agreed that

further investigation of the D.H.110 and Fairey's

designs should continue. After F.44/46 was updated

to F.4/48 in June 1948 the three D.H.110

nightfighter prototypes were ordered, together with

four examples of Gloster's design. Then, on January

3. 1949, it was proposed to acquire four more F.4/48

D.H. 110s for a

common RAF/RN

development programme on armament, radar and

instrument clearance, and two each to N.40/46,

F.5/49 (for an RAF long-range fighter) and N.8/49

(for a naval strike aircraft), bringing the total to

13 prototypes. In March the NR/A.14 requirement was

brought up to date under a new specification,

N.14/49. Four months later three naval D.H.110s were

ordered (two nightfighters, one strike), leading to

concern over the financial implications of procuring

so many prototypes. A joint trials programme for the

RN and RAF was agreed, but in November 1949 the

naval D. H.

110s were dropped for economy, leaving

N.14/49 to Fairey's project. The twin-boom design

seemed a logical advance over its ancestors, the

Vampire and Venom, both of which were conventional

aeroplanes in which the twin booms carried the tail

rather than having it fitted to the end of the

fuselage, thus permitting a very short and efficient

jetpipe. In

|

|

Neither D.H.110 received any

radar or armament. The first had 6,500lb-thrust Avon

RA.3s, while WG240 had 7,500lb RA.7s, intended to be

typical of the Service version but without reheat.

Initial test flying with WG236 revealed flight

characteristics that were much more pleasant than

had been experienced in the D.H.108. There was none

of the ghastly high-speed pitching oscillation that

had made the D.H.108 such a horror; the biggest

problem was found to be "snaking" at high speeds,

which was traced to aeroelasticity (flexing) in the

twin booms. As a result WG236 had its fin area

increased, and the tail-booms were stiffened with

steel reinforcing strips riveted on to the outside

surfaces. The curved fin extensions were faired into

the line of the rudder trailing edge under the rear

of the booms to give extra stability (WG240 had

modified booms of thicker-gauge aluminium alloy).

On

February 20, 1952,WG236 was taken beyond Mach 1 for

the first time, in a dive, by John Derry and Tony

Richards. It thus became the first operational-type

aircraft, the first two-seater and the first twin-engined

aircraft to break the "sound barrier". During 1952

it was decided to develop and fit a fully-powered

all-moving tailplane to provide good transonic

handling. There was no known practical method of

moving a

|

|

|

ABOVE

A sketch of the original D.H.110 concept, designed

to RAF nightfigher Specification F.44/46, with

side-by-side seating and unusual forward-swept tail

surface, both of which would be changed for the

prototype D.H.I 10s.

|

|

|

|

|

|

ABOVE

The second D.H.110 prototype,

WG240, at the SBAC show at Farnborough in 1953.This

head-on view illustrates well the distinctive

offsetting of the canopy to port, which remained on

the later Sea Vixen

|

|

|

comparison, the D.H.110's swept wing was similar to

that of the tailless D.H.108 research aircraft,

while the tail was set high and much closer to the

wing. The tail had to be added to counteract several

problems suffered by tailless aeroplanes (as

distinct from deltas), particularly a gradual loss

in longitudinal stability as the speed dropped.

Designer J.P. "Phil" Smith led the D.H.110 project

until it was transferred from Hatfield to

Christchurch.

After the naval machines were cancelled the

surviving RAF order

|

comprised five F.4/48 nightfighters

(WG236,

WG240, WG247, WG249 and WG252). The contract

for these machines was dated May 26,1950, but WG247

(to be Sapphire-powered),

WG249 and WG252 were all cancelled on June

14,1952. The surviving two were built in the

experimental shop at Hatfield, and WG236's taxying

trials began on September 16,1951. On September 26

chief test pilot John Cunningham made the first

flight, with Tony Fairbrother as his observer, and

the new fighter was first revealed to the

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"The

Farnborough crash was a great tragedy, but should

never be allowed to cloud the fact that the three

D.H.110s proved to be fine flying machines, and

valuable research tools for the Sea Vixen"

|

|

|

|

|

|

"slab tail" manually owing to

the very high loads involved, so any failure of the

hydraulic system had to be safe�guarded against by

full duplication and partial triplication. In 1954

the manual rudders were changed for fully-powered

alternatives using the same system duplication. It

was then found that many of the troubles associated

with yaw autostabilisation on manually-operated

controls were now eliminated and the rudder power

was greatly increased due to the removal of the

large balance tabs. Development of the D.H.110 with

fully-powered controls was largely completed by the

end of 1955.

On July 25,1952, WG236 was

followed into the air by WG240, and the extra power

available to the second aircraft was impressive. It

was also lighter than WG236, so WG240 was selected

as the flying display aircraft for the September

1952 SBAC show at Farnborough. It flew throughout

the week, but on the Saturday went unserviceable

owing to engine problems. John Derry and Tony

Richards went to Hatfield to collect WG236 as a

substitute, and flew this aircraft direct to

Farn�borough for their display. During a manoeuvre

WG236 broke up in the air, killing both crew, and an

engine landed in the crowd, killing another 27

people and injuring 63. The inquiry into this

accident was extensive. The flight had included a

supersonic dive from 40,000ft, with the pull-out

close to the airfield. After a fast pass, Derry

turned to port and made a tight left-hand circuit at

low

(Continued RH column)

|

|

ABOVE

The second prototype in 1952 in its striking

all-black colour scheme, which made quite an

impression on the public during its dynamic

displays.

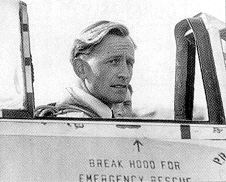

LEFT

John Derry in the cockpit of Vampire W218, which he

demon�strated masterfully at the SBAC show in 1948.

At the time of his death he was D.H. chief test

pilot.

|

level. While straightening out

from this turn about 1.5 miles north-west of the

public enclosure, WG236 disintegrated.

A film taken by a spectator

revealed what had happened. As WG236 banked to the

left towards the crowd its starboard outer wing

detached, immediately followed by the port outer

wing. With only the inner wing sections left, the

rapid nose-up change of trim following the wing

failures caused the cockpit, engines and tail to

detach in secondary failures under an abnormal g

loading. All of this occurred within about a second.

It was found that WG236 had succumbed to the

twisting forces produced while undertaking a

manoeuvre that combined a turn and a climb. The

accident report, dated April 8,1953, stated that the

cause was a combined effect of pull-up acceleration

(associated with turning) and the loads produced by

upward aileron (appropriate to straightening out

from a turn), which had created instability in the

structure. The D.H.110's wing form was the

problem. The

unusual D-nose leading-edge arrangement had

proved fine for the lightweight Vampire and Venom

but could not cope with the heavier stresses

experienced with the much bigger D.H.110.

Before WG240 flew again, in

June 1953, its wing structure was substantially

redesigned. It was fitted with a front spar web and

thicker wing ribs, while the inter-spar stringers

between ribs eight and

(contd. below left)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ABOVE

The awful aftermath of the

crash of WG236 on September 6, 1952.The subsequent

crash report determined that the joint actions of

torsion, shear and bending loads on the starboard

outer wing caused it to twist off, initiating

catastrophic failure of the entire airframe.

RIGHT Test pilots John

Cunningham (left), who made the D.H.I 10's first

flight, and "Jock" Elliot, who flew the maiden

flight of the navalised XF828.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

seven

were reinforced (all of these modifications were

retained on the Sea Vixen). Early in 1954WG240 was taken

in hand to receive the all-moving "flying" tail instead

of the original fixed tailplane and hinged elevator (at

the time it was the only British aircraft so equipped).

The powered rudders, plus cambered "droop-snoot" leading

edges on the outer wings and improved aileron controls,

were also fitted, and it made its first flight in this

form on June 11.

After

the loss of WG236, Gloster's Javelin nightfighter had

become the favoured candidate for the RAF requirement

and was eventually ordered in quantity. The RN's N.

14/49 requirement was withdrawn on July 19,1950, and

Fairey's project was abandoned. A new specification,

N.114T, was intended to replace it but, as a stop-gap,

the RN ordered a navalised de Havilland Venom (Sea

Venom) to fill the unacceptable gap between the Sea

Hornet and the new programme. In January 1952 each of

the tenders to N.114T was found to be unsuitable,

leaving the new all-weather fighter requirement

unfilled. R.E. Bishop at de Havilland designed an

improved Venom, the D.H.116 Super Venom, and a mock-up

was built, but Bishop informed the Admiralty that his

company could not cope with the project because of a

shortage of design staff. In November 1952 he suggested

a navalised D.H.110 as an alternative.

The

D.H.110 was assessed by the Ministry of Supply (MoS) on

March 5, 1953, to see how far a navalised version could

solve the navy's problems. There were doubts whether the

Al Mk 18 radar could be installed, even with a small

scanner, and the strength factors provided by D.H. were

on the bottom limit for fighter duties and would need

modifying for ground-attack operations. The Admiralty

also wanted four Blue Jay air-to-air missiles (AAMs).

The D.H.110 could be adapted to new requirement, NA.38,

and on July 14 the Naval Aircraft Design Committee

recorded formal acceptance of the type to this

specification.

The changes required to the

|

|

|

|

ABOVE

The third prototype,

XF828, was navalised but without folding

wings.

During August 1954 the

name Pirate was mooted for the type but was eventually

dropped, approval for Sea Vixen being made on March

5,1957.

|

sanction was delayed until December 31,1954, when

approval was given for 75 (later 78) aeroplanes.

The

Instruction to Proceed with the full programme arrived

in early January 1955, and the third prototype, the

navalised XF828, was first flown, from Christchurch, on

June 20 by "Jock" Elliot. Production aeroplanes were to

be designated FAW

Mk 20 (soon changed to FAW Mk 1. FAW � Fighter,

All Weather) and receive the Avon 208; the intermediate

XF828 was designated

FAW Mk 20X. Four

Blue Jay AAMs became the weapon choice, with the

Aden guns removed and replaced by packs of Microcell 2in

rockets.

On

September 23,1954, WG240 made a series of preliminary

approaches, overshoots and touch-and-go landings on the

deck of HMS Albion, with the intention of showing the

D.H.110's general handling to be adequate for carrier

operation. Its behaviour was reported as out�standing.

On April 5, 1956, XF828 made its first fully arrested

deck landing, on HMS Ark Royal. By early 1957 the

aircraft had received a large fixed in-flight refuelling

probe, and the first successful in-flight refuelling

with a tanker aircraft at 10,000ft was achieved on

January 10. The Farnborough crash was a great tragedy,

but should never be allowed to cloud the fact that the

three D.H.110s proved to be fine flying machines and

immensely valuable research tools for the

Sea Vixen.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

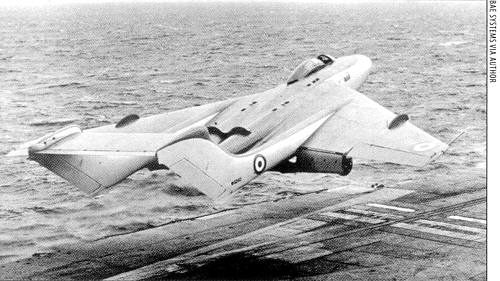

ABOVE In September 1954, Jock Elliot

made a series of touch-and-go landings

aboard HMS Albion with WG240 painted in naval colours

and fitted with

modified long-travel undercarriage oleos. The results

were very satisfactory.

|

|

|

existing D.H.110 were a folding wing, arrester gear and

other normal navalisation fittings, RA.14 Avons, the Al

Mk 18 radar, redesign of both main and nose

undercarriages, changes to the cockpit layout and

fitment of the all-moving tail and larger flaps.

Converting the RAF D.H.110 into a naval aircraft

required a lot of redesign, and most of the drawings had

to be changed. By now D.H.110 design work had been

transferred to Christchurch, and a new specification,

N.139D&P, was written around the aircraft. The standard

for the third prototype, to be constructed from spare

F.4/48 components to a contract dated November 6,1953,

was agreed in

|

August

1953. Specification N.139D&P stated that the D.H.110 was

to operate from HMS Hermes and larger-class carriers,

and its primary role was to be the destruction of enemy

reconnaissance and strike aircraft. Minimum top speed

was now set at 690 m.p.h. at sea level and 610 m.p.h. at

40,000ft, rate of climb at a minimum of 14,000ft/min

(later 18,000ft/min) and service ceiling at 48,000ft.

Production aircraft were to carry a mix of four Aden

cannon and two Blue Jay (Firestreak) AAMs or two Aden

and four Blue Jay.

An

initial approach to the Treasury was made in October

1953 for 100

machines. However, Treasury

|

|

|

The prototype D.H.110, WG236, spent its

brief life painted in a silver scheme with standard

roundels and a swept fin-flash.

Early trials with the first prototype showed the type to

be well in advance of a number of its contemporaries,

including the American Northrop F-89

Scorpion and Soviet MiG-17"Fresco"�

2004 JUANITA FRANZI

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

![]()